Chicagoans Discuss Ordinance and Its Implications for the City

http://www.pbs.org/pov/pov2006/wagingaliving/special_goodman_chi.html

This is a transcript from a PBS documentary interview with Chicago city aldermen Ed Smith, chair of Chicago's Black Caucus, and Joe Moore, chief sponsor of the measure. It also includes ACORN activist Shiren Rattigan-Ouni and Chicago resident Toni Foulkes. They are discussing how they see the big box ordinance affecting the city.

First, I want to share this quote from Moore:

"Unlike us elected officials, Wal-Mart doesn't have to file campaign disclosure reports. But I can tell you that there were full-page newspaper ads financed by Wal-Mart, television ads financed by Wal-Mart. And they made some campaign contributions as well that may or may not have helped them along the way. The bottom line is we were very well organized, but ours is a grassroots effort, theirs was a "throw money at us" effort."

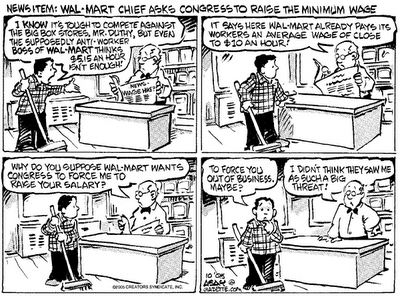

This provides direct evidence of what I have suspected to be the case all along--that Wal-Mart makes campaign contributions that sway policy-makers to vote in their favor. Money is power, but it would be great if those people in power would realize that they have tools to influence those with money, also. It is stated throughout the interview that Wal-Mart has saturated the suburbs and needs to come to the city in order to keep turning a profit and expanding their business. They need it. This means that Chicago can make whatever law it wants to and they will eventually have to adhere to it. It seems like amount of wage increase is a workable item in this debate, and with both sides holding power, a successful negotiation could take place.

Rattigan-Ouni brings up the struggle between media and money vs. people and workers. She talks about money and people as the two ways of obtaining power in America, a perspective that struck a chord with me as I just finished writing my paper on the power of money in American politics. She has more hope for the power of the people than I did in my paper, but the work that ACORN has done does inject some more hope into the effect a grassroots campaign can have on a policy issue like this.

Moore uses an example of FDR's New Deal and Fair Labor Standards Act following the Great Depression to show that a government hand in the economy can cause great economic expansion, despite naysayers. He remarks that we are currently killing the American dream and that people called FDR a socialist at the time, but that didn't stop him from making the necessary changes. He is suggesting we push past any accusations of socialism to prove that this will have a positive affect on the economy.

Foulkes makes a claim that if Wal-Mart was left to its own devices, it would be paying workers as much as they pay them in other countries--she is attempting to strike somewhat of an emotional chord, since many people in the U.S. are against the sweat-shop manufacturing that goes on overseas. This doesn't work, though, because even if the minimum wage is low in the United States, Wal-Mart would never be allowed to pay its workers the penny wages that Foulkes talks about.

The interviewer Amy Goodman brings up an article she read in the Chicago Defender, which discusses a Chicago reverend's opposition to this bill on the grounds that it is equally immoral to deprive people of jobs as it is to pay unfair wages. He makes a good point that some people, probably a lot of people, would be thrilled to take that job for $7-8/hour. I don't necessarily think that is as strong of a moral issue, but it is certainly worth considering. $8/hour is not an unfair wage to a lot of people.

The argument made again and again, however, is that Wal-Mart has the means to be paying more than that $8/hour. They made $11.4 billion in PROFITS last year. And the growing income gap is not helped by the Wal-Mart CEO making $34,999,999 while their average employee makes $16,000.

I can't help but notice everyone's' silence on the factor of prejudice in this issue, not simply in this interview but in all of these articles. The income gap has certainly done a good job of fostering racial and economic typecasting, and the people who make laws are mostly privileged, white, and upper-middle class. Because of stereotypes and assumption, people are prejudiced against low-level unskilled workers. The privileged do not want to support ordinances for poor people, because they assume that poor people are criminals, or that they are poor because they do not work hard enough. Faulkes states in the article that the people getting jobs at Wal-Mart are not felons, they are people who work very hard to try to support families. I think it would be beneficial if the minimum wage campaigns tried to get that fact out there. Working on economic and many other prejudices would help with all the issues I have raised--immigration, poverty, schooling. I realize it may be a bit idealistic, but I am not saying that a) we can solve prejudice quickly, or that b) it is the miracle cure for all of these issues. But it couldn't hurt.